Post written by Erin Sato, Assistant Archivist at Go For Broke National Education Center.

A single devastating event could change everything in an instant. On December 7, 1941, the bombing of Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Hawaii by the Japanese Imperial Army changed the lives of thousands of Japanese Americans forever.

Howard Furumoto, who was a college student at Kansas State University at the time of Pearl Harbor, was among those affected by the events of that unfateful day. In his oral history interview, Furumoto recounts his own experience upon hearing the news of Pearl Harbor:

“December 7th, 1941, I happened to be in this one room. I was the single occupant of this room and, of course, I couldn’t afford a fancy room, I was in the basement room all by myself along with two haole fellas and they had an adjoining—adjacent room; they roomed together, I was alone. And they had their radio on, we didn’t have television back in those days, and it was a squeaky old radio and this announcement came over the radio and I heard it. Franklin Delano Roosevelt coming on and he announced, of course, that Pearl Harbor was attacked and then he made declaration that “THIS IS WAR!” That’s what I heard and that was really devastating. Yeah, my whole world came to a stop then.”

From that day on, Furumoto went from being an ordinary college student to a feared and hated “Jap”:

“I had many friends, you know, before Pearl Harbor but then after Pearl Harbor, of course, I was, I was Japanese, a Jap to them. They made no distinguish—distinction, yeah. Even the places where they served meals, places where they cut hair, barbershop, we couldn’t get the proper service. I was turned down by the barbershop, they couldn’t cut—he wouldn’t cut my hair anymore; the same barber. Go to a restaurant, they wouldn’t serve you.”

This response towards Japanese Americans resonated throughout the entire nation. What manifested from this wartime hysteria was President Roosevelt’s authorization and implementation of Executive Order 9066, which allowed for the forced removal and incarceration of 120,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast. In addition, due to fear of sabotage, the government reclassified all Japanese Americans who were eligible for the wartime draft from 1A (available for military service) to 4C (enemy alien). However, this did not stop the Nisei from proving their loyalty and volunteering to enlist into the United States Army. Some Nisei went through extreme lengths to volunteer. Tsuneo “Cappy” Harada mentions in his oral history interview, how he hitchhiked 35 miles from his junior college to Camp San Luis Obispo to enlist.

Those living in Hawaii at the time of the attack endured a different course of events that contrasted the experience of their counterparts living on the Mainland. For instance, all soldiers of Japanese ancestry who were serving in the Hawaii Territorial Guard were disarmed and discharged from service. Undeterred, this did not stop them from volunteering their services towards the war effort.

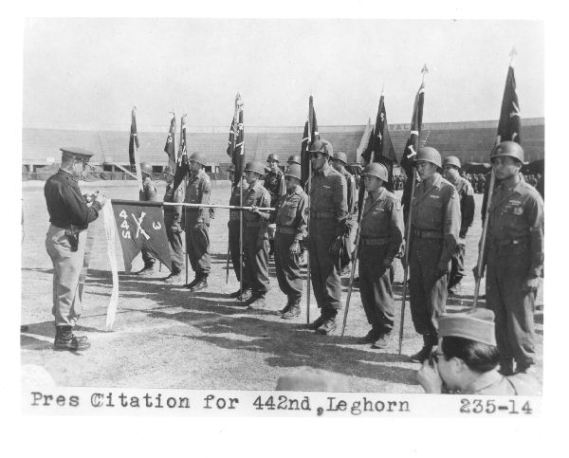

By gathering a number of volunteers, this group was formed into the Varsity Victory Volunteers (VVV), which was attached to the 34th Engineer Battalion. As a civilian labor battalion, the VVV worked hard to construct roads, build barracks and water towers–contributing any type of labor work to help. The dedication and hard work conveyed by the VVV led to the creation of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

The bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941 changed the lives of the entire Japanese American population in the United States. The situation that the Nisei were put into forced them to take a course of action; instead of letting the response of the American public hold them back, they focused on reaffirming their American identity by offering their services and sacrificing their lives to fight for the country that doubted their loyalty. It is this type of patriotism and willingness to “Go for Broke” that made the 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate) and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team the most highly decorated military unit in United States military history.

In our presentation, we first gave a background about the history behind the Nisei soldiers’ experience during World War II.

In our presentation, we first gave a background about the history behind the Nisei soldiers’ experience during World War II.